James Frederick Masterton (1881-1917)

Guernsey mariner

died at sea 29th March 1917

aged 35

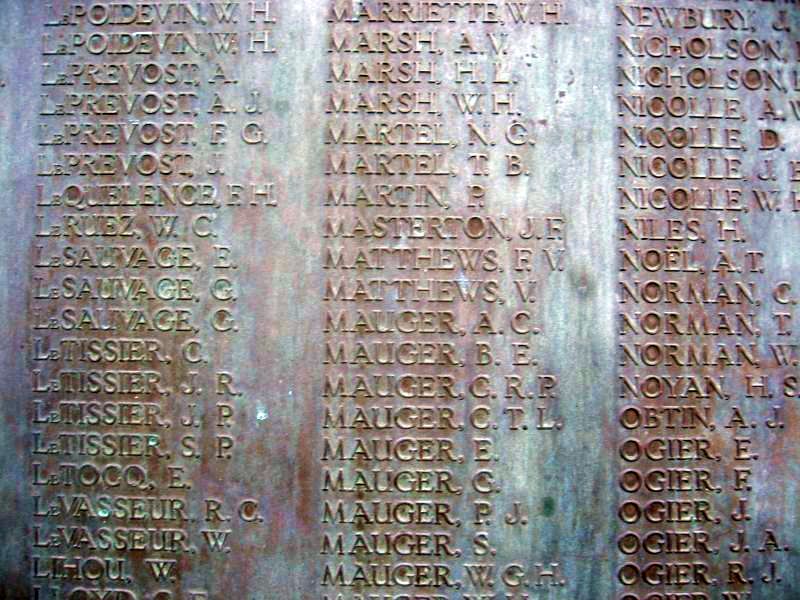

St. Peter Port War Memorial, Guernsey

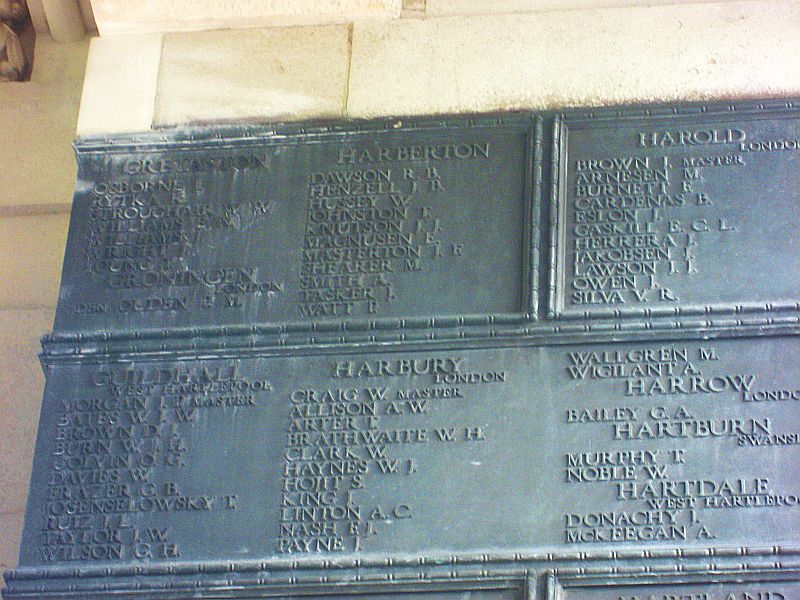

Tower Hill Memorial, London

Son of James Masterton and Louisa Amy Loveridge

Husband of Elise A LeRiche

Father of six children

Guernsey, Channel Islands

aged 35

St. Peter Port War Memorial, Guernsey

Tower Hill Memorial, London

Son of James Masterton and Louisa Amy Loveridge

Husband of Elise A LeRiche

Father of six children

Guernsey, Channel Islands

Thanks are due to Keith Pike, Guernsey, for transcribing and providing the source articles from Guernsey newspapers.

Genealogy

James Frederick Masterton was the third of nine children born to James Masterton, master mariner, and Louisa Amy Loveridge, who had married in 1876 in Guernsey. The first Masterton to relocate to Guernsey was captain John Masterton (1815-1892), eldest son of a butcher in Montrose, who married Jane Symes and then Mary Phillips, both from Bridport, Dorset. John moved to Guernsey with Mary and two children in 1849 or 1850. James Frederick Masterton therefore belongs to the large group of Mastertons that flourished in the Forfar and Montrose area. He married Elise Amphitrie Leriche in 1902 in Guernsey, and they had at least four children. Fuller details of his extended family can be found at this link.

His War

James Frederick Masterton, seaman, was born in St Peter Port, Guernsey, His career as a pilot was cut short after he lost his certificate at the age of only 27. He later served as mate and was second mate aboard the collier "Harberton" when it was either torpedoed or hit a mine off the Yorkshire coast in 1917. His name is recorded on War Memorials in Guernsey and London.

The "Harberton" was built for J. & C. Harrison, London; Yard No 185; Launch Date: 16/06/1894; Date of loss not certain, probably struck a mine laid by UC.31; All 15 lives lost, including master. The "Harberton" left Blyth on Thursday 29th March 1917 bound for London with a cargo of coal. The ship was never seen or heard of again and it is presumed to have struck a mine laid by a German U-boat with the loss of all 15 crew. Estimated position of loss: Off Robin Hood´s Bay; North Sea, Shipping Lane South of Blyth. One of ten Cory Colliers involved in the London coal trade, lost off the Yorkshire coast to German U-boats or mines they had laid during WWI, the others were: Brentwood, Hurstwood, Ocean, Vernon, Sir Francis, Harrow, Corsham and Highgate. The Deptford was also mined off Scarborough in 1915.

East Coast Shipwreck Research

Carl Racey

cited on website www.wrecksite.eu accessed 9 December 2017

Harberton SS was a 1,443grt, British Merchant steamer. On the 30th March 1917 when in the North Sea she was probably torpedoed without warning and sunk by submarine, date uncertain, listed as 30th?. 15 lives lost including Master. Vessel was on route from Blyth to London.

British Vessels Lost at Sea. HMSO

cited on website www.wrecksite.eu accessed 9 December 2017

The collier Harberton SS left Blyth on March 29th, 1917, for London, with a cargo of coal. She was mined in the North Sea by German submarine UC-31, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Otto von Schrader, and sunk. UC-31 had been launched on 7th August 1916, and commissioned on 2nd September 1916. It sank 38 ships with a total tonnage of 51,017, of which only one was a warship, the 1,025 ton destroyer, HMS Magic, damaged on 10 April 1918 by a mine laid by UC-31. It outlasted the war, being surrendered on 26th November 1918, and was finally broken up at Canning Town in 1922.

uboat.net

cited on website www.wrecksite.eu accessed 9 December 2017

His name is recorded on the St. Peter Port War Memorial, Guernsey

His name is also recorded on the Tower Hill Memorial, London as one of the crew of the "Harberton"

Other Sources

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Medals Index Card: Mercantile Marine Medal; British War Medal. National Archives. BT 351/1/89520

- S.S. "Harberton" (London) Wreck Site

- James Frederick Masterton in IWM Lives of First World War

Pre-War Sources

The Star

J Frederick Masterton, pilot, was actioned at the instance of John S Carey, Esq, Assistant Supervisor, to see himself condemned to pay a fine at the discretion of the Court besides the cancelling of his certificate, for having on the night of January 23rd last infringed Article 15 of the Law relating to Shipping by having, whilst in charge of the International caused her to touch a rock known as the Musée and then caused her to become a total wreck on the Barbé, through his fault, negligence or incompetency. Advocate H H Randell, who appeared for the accused, asked that witnesses be ordered.

The Star

Guernsey

30th January, 1908

J Frederick Masterton, pilot, was actioned at the instance of John S Carey, Esq, Assistant Supervisor, to see himself condemned to pay a fine at the discretion of the Court besides the cancelling of his certificate, for having on the night of January 23rd last infringed Article 15 of the Law relating to Shipping by having, whilst in charge of the International caused her to touch a rock known as the Musée and then caused her to become a total wreck on the Barbé, through his fault, negligence or incompetency.

On Thursday week Advocate H H Randell, who appeared for the defendant, asked that witness be ordered. Today ten witnesses were sworn-in.

H M’s Procureur said Masterton was actioned for having infringed Article 15 of the Pilot Law by causing the International to touch the Musée rock and then become a total wreck on the Barbé at the south of Jethou. The law provided that he fine to be inflicted should be left at the discretion of the Court, besides the cancelling of the defendant’s certificate for a fixed time or entirely. Masterton took charge of the International on Wednesday evening, the 22nd January. There were only three witnesses for the prosecution, viz, the master and mate of the International, besides Captain Jones, who was in the habit of examining pilots and fully conversant with the tides and rocks. It would be shown that Masterton was put on board the International by the Assistance, and at that time the harbour lights and Hanois light were visible. At the time the wind was southerly, fair for entering St Peter Port. A very interesting and important question concerning the set of the tide would be raised. At the time there was a tide setting to the N E, and unless there was a wind sufficiently strong the vessel would drift towards the fair way, the Captain blamed the pilot for not waiting for the ebb tide which would have taken them clear of the Ferrieres. The learned speaker then produced charts of the coast and explained the position of the rocks and the wreck. There would doubtless be some discrepancy in the evidence to the effect that had the accused been allowed to manage the vessel as he wished after touching the Musée, she would probably have been saved.

Captain Jones then explained the charts and said Masterton was sworn –in Pilot on December 5th 1907. The International was about 2½ miles from St Martin’s Point when Masterton boarded her.

Captain Edwin A. Court said he was master of the Brigantine International which was coming to Guernsey from Briton ferry with a cargo of coal on the 22nd January. Witness said he was 49 years of age and had been coming to and from the Island since the age of about 14. He held a mate’s certificate dated 1878. The International belonged Mr Goldfinch, of Whitstable: Towards the evening of the 22nd inst, the International opened St Martin’s Point and signalled for a Pilot who was put on board by the tug Assistance at about 7 PM. At the time the wind was about south and the ship running at about 3 or 4 knots. There was a “nice commanding” breeze. As soon as the Pilot came on board he took charge of the vessel. The breakwater light was then to the starboard side and the Pilot put her on the port tack. He then ordered the mainsail to be taken in. so far witness saw no harm in taking in any canvas. The Main topsail and flying jib were then hauled down. The boat was then put out to make Preparations for warping when they entered the harbour. The Pilot then remarked that the vessel was going too fast for the boat’s safety. After a while the pilot said she would go in the harbour very nicely and at that moment witness heard a rustle on the water and he asked if it was more wind or the tide running. The mate at that moment pointed out something on the port beam which was found to be the Lower Head buoy. The Pilot thereupon ordered the anchor to be dropped, and the port anchor was let go as quickly as possible. Witness afterwards went to the helm, and finding the Pilot was not there he (witness) therefore took the helm and rounded the vessel with the bow facing St Martin’s Point. Witness then went forward and assisted with the anchor which was dropped with 30 fathoms of chain. The vessel was immediately brought up. The Pilot was then in the forward part of the vessel and the helm had been left hard to starboard, witness then eased it. By that time the Lower Head buoy was out of sight. The night was fine and clear. The Pilot said he had not brought the vessel up because he feared danger, but to prevent her from running up the Big Russel. It was then between 8 and 8.30 P M. they remained at anchor until about 11 P M. in the meantime the Pilot waved the stern light for the tug which came out towards the International. The tow ropes were prepared, but the tug passed close by and did not hear the Pilot who hailed them. The tug returned to the Town Harbour, and left the International which was dragging her anchor towards the north east. When witness mentioned this to the Pilot he said that by his bearings she was not doing so. At about 11 P M the Pilot ordered the anchor to be pulled up. Witness then took the wheel and the Pilot went forward to help to take the chain in. when about five fathoms had been pulled in witness saw a beacon astern which he could not distinguish at the time. The Pilot was called aft and the beacon pointed out to him, but he did not reply. Witness thought there was no room to “slip” and thought the vessel was safer at anchor. He suggested to the Pilot that all the canvas should be brought in and the ship allowed to be quiet where she was until the turn of the tide. The anchor was then holding well and the vessel was still. They remained in that position until about 12.30. There was still the same breeze, in fact from 7 to 12.30 there was no variation in the force of the wind, although the direction may have varied about a point. At 12.30 the Pilot said the western tide would take the ship away from the rocks and he ordered the anchor to be heaved up. Witness looked over the bow and found the vessel lying to the order side of the anchor and concluded that the tide would take the ship away from the rocks and he ordered the anchor to be heaved up. Witness looked over the bow and found the vessel lying to the other side of the anchor and concluded that the tide was not sufficiently strong to take the ship to windward. He told the Pilot of this and after consulting they decided to wait a little longer. At about 12.45 the order was again renewed and the anchor was drawn up. The Pilot was assisting at the windlass and witness was pulling in the chain. Whilst this was going on the vessel struck aft. The shock was not very violent. When the shock occurred witness ran to the stern and saw that the rudder was unshipped. The lower fastenings of the rudder had snapped and the rudder held on by the fastening on the deck only. The pilot then ordered the anchor to be “slipped.” This was done, and the anchor with 15 fathoms of chain went to the bottom where it remains. The vessel was then pointing towards the Barbé rock. By manoeuvring the vessel backed clear of the outer rock, but she sailed on to the edge of the inner rock. All the crew were on board at the time. When the vessel was found to be going on the Barbé rock all hands got into the boat. The Pilot was in the boat before anyone else. The vessel was unmanageable, having no rudder. From in the boat witness watched the vessel go on the rock. The mate was the last man to get in the boat. When she seen to settle on the rock witness went back to her and proceeded into the cabin to save the ships articles among other things. The ship was practically “done for.” When the crew left her the pumps were not sounded and witness did not know whether the vessel was making water or not.

By Advocate Randell: Witness said the Pilot did not steer towards Fermain Bay. He kept out about two miles or more from St Martin’s Point. The vessel was really too far to the east of St Martin’s Point and witness told the Pilot so. The anchor was dropped about two r three minutes after the buoy was seen. The vessel kept drifting to the north-east until about midnight when she turned with the stern towards St Peter Port. When the pilot first ordered that the anchor should be heaved up, the vessel was heading to the S W. when the beacon was sighted she was only about her own length away from it. The beacon was on the starboard quarter, but later it was seen clear of Jethou. When the pilot first suggested slipping the anchor witness refused to do so as he thought the vessel was after where she was. At 12.45 when the order was given for the anchor to be hauled up all hands set to work on it immediately, but the anchor was never got off the ground as the vessel drove in shallow water faster than the chain could be hauled in. when the vessel struck, witness was standing forward. She gave two or three bumps in the after part. She did not strike for ward at all. She did not remain on the first rock, but drifted further inwards on to the Barbé. At the time the ship’s head was about N E towards the Barbé. The Pilot’s attention was drawn to the fact that the rudder was gone as soon as witness noticed it. Before the crew abandoned the ship the Pilot spoke about the upper top sail being furled, but no one would venture up the mast with the ship in the condition she was then in. the Pilot got in the boat before witness after the vessel struck the rock. Some of the crew were in the boat at the time. After the vessel struck the Barbé witness rowed back to her and went on board. The court adjourned from 1.15 to 2.15 P M.

Charles Budden, mate of the International, said he had been on board that vessel for four years. He had been in and out of St Peter Port Harbour many times, but did not know the rocks. He remembered that when Masterton came on board on the 22nd January there was just a nice wind for such a vessel as the International, but he did not notice the position of the vessel as he was busy about other duties. Witness was on the quarter deck when he saw an object in the water on the port beam and asked whether it was a buoy or a boat. The Pilot was steering the vessel at the time. Orders were then given to let go the anchor. This was done as quickly as possible and the vessel was brought up. The operation did not take long as it was kept ready. The anchor caught at the bottom firmly. After a while the two topsails were stowed. After considerable time the remaining sails were taken in. witness could tell by the chain that the vessel was dragging, although he took no marks, and the whole 30 fathoms was paid out. There was a nasty swab with the tide. Everything was clear, the weather being very fine. Witness next saw the Pilot at the stern waving a light for the tug which came from St Peter Port, and after running close alongside she steamed away again and the Pilot made further signals which, however, were not answered. Witness then burnt a flare. The crew were waiting for orders, when presently witness heard the order “heave away.” About five fathoms of chain was hauled in when witness was told to stop. He did not know why he was told to stop heaving, but he immediately noticed a beacon at the stern. Nothing further passed until fresh orders were given to get the ship under weigh and the crew continued heaving the anchor. Orders were then given to loosen the topsail, and there was a man loosening the upper sail when the vessel struck a rock with her heel. The shock was fairly severe. At the time the vessel struck the anchor was still on the ground, and then orders were given to slip the chain which was done immediately. It rather too much of a hurry over things for witness to take notice of times or tides. After the ship struck, the foretopsail and flying jib were put up to try and back her off. The rudder was then hanging by the upper gudgeon only, the other three having broken off when the vessel struck the rock. The vessel was running towards the reef of rocks. Witness did not hear the Pilot give any further orders after the vessel struck. As soon as the vessel was found to be hopeless the crew left her. She was then on the Barbé rock. There was no shook, but she gradually got on with the eddy tide and finally settled there. Witness went in the cabin to save what he could and when he returned he found all hands in the boat. When the vessel was seen to be fast on the rock the crew returned to her and fetched away more of their belongings. After the anchor was slipped all the orders given by the Pilot were carried out as far as witness could tell.

By Advocate Randell: When first witness noticed the buoy it was about half a mile away from the vessel. When the Pilot came aboard she was travelling at the rate of about three or four knots. The first time the crew left the vessel witness could not swear that she was on the Barbé. After they had got into the boat there was some talk about the vessel going astern. Witness could not swear that the Pilot did not suggest that he might save her. In reply to a question by Advocate Randell, witness said there was no question of paying off the hands on arrival at Guernsey. The pumps had to be used every night. The last time witness left the vessel there was about 2ft of water in the cabin.

Captain William C Jones, Harbourmaster of St Peter Port, said he had never been examined concerning the rocks and dangers of the Island. He had however, had practical experiences, having been at sea for 35 years and master of vessel for 26 years. Having had considerable experience in local waters he knew the marks and cross marks well. Witness was President of the Pilot’s examination Committee. On the day in question the tide was high at 9.20. the tide ran in an easterly direction as far as St Martin’s Point, and then one stream branched off up the Small Russel about N E, and another stream went up the Big Russel E N E. at the time the Pilot boarded the International she must have been three miles at least from St Martin’s Point, otherwise the Hanois and breakwater lights would not have been seen together. The breakwater light was on the starboard bow of the vessel and the master was evidently “hugging” the coast to counteract the tide. The Pilot should not have placed the light on his port side as the tide was carrying him east. The breakwater light should have been bearing to the N and E, as the wind was astern of the vessel which enabled her to keep her course, unless it was very light, in which case she would go with the tie. Had there been less wind the Pilot should have steered more to the eastward, and if the wind was not sufficiently strong to counteract the set of the tide he should either have gone up the Big Russell or dropped the anchor. Witness could not account for the Pilot bringing the vessel so near to the buoy and then to the Musée. With the wind and tide as it was the vessel should not have got in that position. According to the evidence witness concluded that the vessel was lying with her keel over the Musée when at anchor and when the tide lowered the vessel, grounded on the rock. From the Hanois to St Martin’s Point the tide ran up and down the Russel and changed at the half-tide. At half-tide it ran at its full strength around St Martin’s Point. Witness thought the Guernsey tide was 10 minutes later than that of Jersey.

By Advocate Randell: Witness proceeded to give further details as to the set of the tides on the east coast. At high water the tide would run at about three knots. Between the Lower Head buoy and the Musée rock there was plenty of water and by proper management the vessel should have been worked out of danger into safer waters. There were about three cables lengths from the Musée to the Barbé. There should have been room to turn in this distance had orders been properly given and properly carried out and the vessel in good condition. By H M’s Procureur: A vessel with her rudder “shipped” could neither “wear” or “stay” in so small a space. She would require plenty of room and very careful handling.

The Court adjourned the further hearing of the case until next Thursday.

The Star

Guernsey

8th February, 1908

James Frederick Masterton, Pilot, was again called, and was actioned at the instance of John S Carey, Esq, Assistant Supervisor, to see himself condemned to pay a fine at the discretion of the Court besides the cancelling of his certificate, for having on the night of January 23rd last infringed Article 15 of the Law relating to Shipping by having, whilst in charge of the Brigantine International, caused her to touch a rock known as the Musée and then to become a total wreck on the Barbe, through his fault, negligence or incompetency.

The evidence for the defence was proceeded with.

Captain John Gillman, master of the assistance, said he was a certificated Pilot. On the evening of January 22nd witness was in charge of the Assistance and put Pilot Masterton on board the International between 7.20 and 7.45. The latter vessel was about five miles from the breakwater light or 2¾ miles from St Martin’s Point. The Hanois just visible. After Masterton was put on board witness saw nothing more of the International until when the Assistance went around the Lower Head buoy to look for a steamer. The International was then brought up in a safe position. Witness heard no one hail him, neither did he hail anyone. He saw no flare. The wind was about the same all the evening. When Masterton was put on board the tide was running at the rate of about four miles to the E N E.

By H M’s Procureur: When the Assistance went out towards the International she was lying about N E of the Lower Heads buoy.

Messrs J Langlois and Miller were called by the defence, but did not appear. These were the two witnesses who were confronted by the mate last week.

M Gaston Le Valois said he was a passenger on board the International on the day in question. When the vessel was brought up at about 11 o’clock the anchor was hauled in as quickly as possible. After the vessel struck witness was told to “put on his best clothes” as there was going to be danger. All the crew “jumped into the small boat.” Two of the crew were in the boat first. The first time the crew left the boat the Captain was the last to leave the vessel. The Pilot got in the boat after the crew just before the mate and the Captain. When all had got in the boat the crew commenced to pull for Town and then the Pilot suggested going back to the ship and said that she might be saved if the crew all went back. The Captain then suggested that everyone should go back and save all they could. The vessel was then afloat. Most of the crew returned to the vessel and witness and one of the crew remained in the small boat. He did not hear the Pilot give any orders. The second time the Captain and the Pilot got into the boat together. The Pilot then seeing the position of the International suggested that all hands should go on board and try and save her, but the crew refused.

By H M’s Procureur: Witness signed the Articles on board the International whilst on the journey to Guernsey.

Advocate Randell then asked for permission to call witnesses concerning the present position of the rudder of the International.

Permission having been given, Messrs Daniel De Carteret and Clifford De Carteret were then called and sworn in.

Daniel De Carteret said he was Master of the Pioneer, a salvage steamer, engaged in salving the International. Witness had been out to the scene of the wreck every day, except Tuesday, since Saturday last. Witness had had a thorough overhaul of the keel of the International and saw nothing wrong with the rudder or the keel of the vessel. The rudder is hung on all the “gudgeons.” There was about five feet of water over the rudder when witness saw it. The rudder was not away from the stern post. It was impossible to see daylight between the stern post and rudder. It was an incorrect statement to say that the three lower “Gudgeons” were broken.

By H M’s Procureur: The International was lying with her deck perpendicular. At half-tide there was a large portion of the keel uncovered.

Clifford De Carteret said he was a deck hand on board the Pioneer. The Rudder of the International was in its proper position. Had the rudder been unshipped witness could have seen it. The vessel was lying on her port side with the rudder turned backwards.

By the Bailiff: The keel is never uncovered. At low tide about 5ft of water lies over it. The upper part of the rudder was about two or three feet under the water. H M’s Procureur regretted that he had not been apprised of this evidence.

It was possible that the Captain and mate made a mistake. A diver might be sent to examine the rudder later on when the tides suit.

The Bailiff thought the question was a very material one. The hearing was postponed sine die.

The Star

Guernsey

13th February, 1908

James Frederick Masterton, Pilot, was again called, and was actioned at the instance of John S Carey, Esq, Assistant-Supervisor, to see himself condemned to pay a fine at the discretion of the Court besides the cancelling of his certificate, for having on the night of January 22nd last infringed Article 15 of the Law relating to the Shipping by having whilst in charge of the Brigantine International, caused her to touch a rock known as the Musée and then to become a total wreck on the Barbé, through his fault, negligence or incompetency.

It will remembered that on Thursday last the Master and one of the crew of the salvage steamer Pioneer were called by the defence and gave evidence to the effect that the rudder of the International, was not unshipped, the Captain and mate of the latter vessel having previously declared on oath that the rudder was hanging by one gudgeon only, the Court decided it advisable to again postpone the case to enable amn official visit to be made to the International so as to ascertain which statement was correct.

This was done yesterday, when the Vixen, carrying Captain Jones, Harbourmaster, Mr D Clancey, States diver, and others, proceeded to the spot.

Today, Mr Daniel Clancy, States diver, was called and said he proceeded to the scene of the wreck yesterday at 1.30 and went down to the vessel. It was then low water. The vessels was lying on her port side and witness found that two of the lower “pintles” were broken. The gudgeons themselves were all right on the sternpost, although the rudder itself was about six or eight inches away from the sternpost. Witness did not examine the keel of the vessel as he had trouble to get to the rudder owing to the growth of currie and weed. He could walk on the left (starboard) side of the vessel. There was about 14 or 15 feet of water over the rudder at the time witness went to it. The “pintles” were about 6 inches long. These may have been snapped as the vessel fell over after striking. Witness was of opinion that she fell over with a heavy bump. He did not think it was likely the “pintles” were broken through the vessel striking or the bottom of the rudder touching a rock. Witness could not swear that the bottom of the rudder did not touch a rock; but it appeared clear from splinters, although covered with growth. The rudder did not appear displaced. Had the vessel been righted the rudder would have gone back to its proper position.

Captain Jones explained that there was a “woodlock” which keeps the rudder of a vessel from unshipping.

By Advocate Randell: Witness would not abandon a vessel because two of her gudgeons were gone.

Prior to his address for the defence Advocate Randell read Article 15 of the Law relating to Pilots which provides that the penalty cannot exceed £50 stg, for causing a vessel to be wrecked. Counsel admitted that there was an error of judgement at the outset, from the time Masterton took over the International, to the time she was at the Lower Head Buoy. At the time he boarded her, the vessel was sailing at what was termed a nice pace. All was well and she was in the right direction. In fact Masterton himself admitted that there was a “commanding” breeze and that the vessel was going too fast to lowere the small boat.

The Bailiff remarked that a “commanding” breeze meant that a master could do whatever he liked with the vessel.

Advocate Randell agreed that a commanding breeze meant a breeze in which a vessel could be commanded in all directions except at certain angles. At the onset the Pilot’s duty should have been to cross from the Great Russel into the Small Russel. To do this he should not have pulled down the mainsail so soon. True he asked on two different occasions if it should be pulled down, and the first time he said no, but the second time he assented, but it was too soon. It was possible that during the evening the breeze died down to a certain extent. He could not account otherwise for the tide taking the vessel to the east. The speaker asked the Court to remember that the Pilot was at the mercy of everyone on board the ship. He was put on board a vessel by the tug and left there alone, and he was the only one who could present a defence, but unfortunately the law prevented that the evidence on oath should be taken. He (the speaker) could not help feeling that the master and mate of the International, only looked to clear themselves. Many questions depended upon the result of this case, among which were the master’s certificate and the insurance. Far from bringing the breakwater light on the port side of the vessel the pilot steered the vessel towards Clarence Battery, bringing the light two points to starboard. It must be admitted that according to the result he should have steered more towards Fermain Bay. She did not get in the Little Russel as the tide carried her towards the Ferrieres. From that point Mr Randell could not accept the statements of the master or mate of the International, the anchor was dropped either rightly or wrongly. It must, however, be remembered that the hoisting of canvas was not a matter of seconds but of considerable time. Once the anchor was dropped the vessel dragged either through not having sufficient chain or some other cause. The Pilot had anchored to wait for the opposite tide to make and carry him away from the rocks at the south of Jethou. The Court had been told that the port anchor was dropped and that the Pilot had said he was not bringing the vessel up on account of danger, but to keep her from going up the Big Russel. The further the vessel got to the north the the nearest she got to the Ferrieres. The Pilot knew very well where he was and he thought fir to anchor in safety, although it was admitted he had to do this through an error of judgement at the beginning. Had not the anchor dragged the vessel would have been perfectly safe and when the tide turned she would have been easily brought in. The Court would have to weigh carefully whether they could find Masterton guilty of negligence or want of skill. The Assistance was seen to come towards St Peter Port harbour and signals were made to her. She then proceeded towards the International and the speaker could not account for those on board the former not seeing or hearing the signals of those on board the latter. The crew of the International had even got the tow-rope ready, thinking they were going to be towed in. From this point the defence was that the Pilots orders were not carried out, but those of the master were. The post or beacon that was seen by the witnesses was a post on the Demi-Ferrieres and the rock which the vessel struck first was one to the S W of the post. The question then presented itself whether the rudder was then rendered useless or not. The Captain of the vessel said the three lower gudgeons were gone, but counsel pointed out that his theory was that having struck the Musée the master and crew thought it would be a good opportunity of losing the vessel, and therefore from that moment onwards they would not help the pilot. All his orders were disobeyed and he was left single-handed.

The Bailiff, interrupting, observed that Mr Randell was making a serious charge.

Continuing, Mr Randell and that although it was midnight the master and mate asked the Court to believe that they could see that the three lower gudgeons had gone. The Court should consider the fact that it was dark and the master claimed that he could see down the rudder hole and right under water. As a matter of fact the three lower fastenings were not gone. The first one that could be seen was intact. The diver had said in his evidence that he thought the “pintles” had broken by the vessel falling over heavily. The defendant strongly denied that the rudder was unshipped when the vessel touched the Musée rock as the Pilot himself worked the tiller after and it answered. Assuming, however, that it was true, did the crew do their duty afterwards? The Captain, himself, admitted that everyone got in the small boat when the vessel went towards the Barbé and they watched her drift thereon. This made the case very serious. The speaker had never heard of a master and crew abandoning their vessel until she was hopelessly firm on the rock. Had the crew remained on board and carried out the Pilots instructions the vessel would not be where she is. The accused did not cause the vessel to strike the Barbé and counsel asked the Court not to find him guilty of the charge and not to accept the evidence that she had no rudder and was unmanageable. In some parts of the evidence it was admitted that after the vessel had touched the Musée, the Pilot gave orders concerning the sails so as to get the vessel out into safety, but the crew were apparently frightened and did not obey the orders. If the topsail had been set the vessel would have soon been got under control and taken into safety. The witness Le Valois had said in evidence that the crew told him to put his best clothes on as there was going to be danger. He also said that when once in the small boat the pilot advised going back to the ship to try and save her and all the crew refused to do so. The Pilot said the vessel could be got out safely if the crew would only go back and abbey his orders, but they took no notice of him. It was important to know if the vessel was manageable or not from the time she struck on the Musée. It was very probable that the rudder had broken since she struck where she is now. The fact of one or two gudgeons giving way did not make the rudder useless. It was hard that Masterton could not give evidence himself, as he would have given the Court his version of the affair. There were times when men were placed in very difficult positions and the speaker contended if the crew had obeyed the Pilots orders everything would have been right. Mr Randell said he had had to put such a case as this forward, perhaps awkwardly, but he placed his client in the Court’s hands and asked them to judge if he were guilty of negligence, want of skill or not. The International struck the Musée as the result of dragging her anchor and she struck the Barbé through the crew disobeying orders. H M’s Procureur having addressed the Court, the judgement of the Court was postponed until Monday.

The Star

Guernsey

20th February, 1908

Frederick James Masterton, Pilot, appeared for the fifth time in answer to the charge of causing the Brigantine International to touch the Musée rock and then became a total wreck on the Barbé whilst in charge of the vessel on the 22nd January last.

On Thursday last we published Advocates Randell’s address for the defence.

On that day H M’s Procureur said the Court would have to consider if there was want of skill or not. The Pilot, Masterton, was guilty of two faults; first, by bringing the vessel where she was in danger, and secondly, heaving the anchor too soon. It was admitted that the weather was clear and the wind favourable. After a while the vessel was brought up near the Lower Heads buoy and he should either have run up the Great Russel or anchored. The Pilot chose to anchor, but this he did on a bottom which was not safe and for which every Pilot should make allowance. Counsel for the defence had said that the vessel was anchored in a place of safety. The place would have been secure had not the anchor dragged. At 12.30 the Pilot ordered that the anchor should be heaved up, but the master, looking over the side of the vessel, said the tide was not running strong enough to take her out of danger. The anchor was consequently left down for another quarter of an hour. The speaker contended that the master’s evidence was corroborated in every material diver who said that two of the pintles had gone, and the speaker suggested that the Captain and mate of the International would not be so bold as to give false evidence. The mate had said he did not hear any orders given which were not obeyed. The master admitted that one of the crew was ordered to see to the top-sail and he refused to do so. The pilot did not stick to the vessel as he should have done. H M’s Procureur admitted that the finding of the Court might wreck the life of a respectable young man. This would be most regrettable, but the lives of the public had to be taken into consideration.

Today (Monday) the Bailiff said he and the Jurats had had an opportunity of reading not only their own notes, but those of the shorthand reporter. There were several questions which had arisen which the speaker would like explained. Captain Jones, Harbourmaster, then produced a chart and explained several points.

The Bailiff asked whether, granting that the International was to the east of the Teed Aval when the Pilot boarded her, it was prudent and seaman like to have brought her near the Musée or Demi Ferrieres.

Capt Jones said it was not. The vessel should never had got near the Lower head buoy. In the first place the vessel should have been given more canvas and cleared in the open.

The Bailiff asked if it would have been dangerous to try and run up the Big Russel from the point where the anchor was dropped.

Capt Jones replied in the affirmative.

Advocate Randell called attention to the fact that the mainsail was off at that time and the anchor was dropped with a view to averting danger.

Capt Jones remarked it depended upon the distance the vessel was from the buoy.

The Bailiff said the Court could not help giving themselves some anxiety to do justice to the young Pilot who was on his trial and to whom an adverse decision must be an event of serious consequence. They must bear in mind that he could not be put on oath, and he was as regarded all questions which the interests of the master and crew of the International were concerned entirely at their mercy. He was only one man against several and should be given the benefit of that fact. At the same time they must bear in mind that Pilots duties are of a very responsible nature. Every ship entering this port must have a Pilot on board, either their own or take up one within a certain radius before coming into the port. Every Pilot must be skilful, careful and able to undertake that in taking over the navigation of a ship she shall be manoeuvred with due skill and care. Neglect of either of these particulars constituted the charge brought against Mr Masterton. In referring to the Ordinance against which the accused had offended, Sir Henry pointed out that it dated from 1903 and had been in force ever since and renewed periodically. Article 15 of that Ordinance said that any Pilot causing damage to a vessel by his negligence or want of skill shall forfeit the whole of his salary and be subject to damages not exceeding £50 and a fine at the discretion of justice, besides having his licence suspended or cancelled. Those were the risks run by Masterton if he was guilty of what he was charged. In the cause, which was at the instance of the Assistance-Supervisor with the Crown officers jointly, he was actioned to be adjudged to pay such fine as the Court might think necessary and also to see the Court order the suspension or withdrawal of his licence for having, whilst in charge of the International, by his negligence or want of skill caused the said vessel to touch the rock known as the Musée and afterwards to become a total wreck on the Barbé. The Court had been carefully shown where the rocks in question lie. It must be proved that there was negligence or want of skill in the duty which Masterton had undertaken, there were four questions which Sir Henry asked the Court to decide upon.

1st: Was there on the part of Masterton want of care or skill in taking the course he did which brought him to the Lower Head buoy?

2nd: Was there negligence or want of skill in casting the anchor when the vessel was found to have passed the Lower Head buoy?

3rd: was there negligence or want of skill in heaving the anchor before the western tide had set in sufficiently strong to float the vessel away room the rocks?

4th Was there negligence or want of skill at any subsequent time?

This last question involved a number of minor questions which included:

A. Was the accused guilty of negligence or want of skill in slipping the anchor when he did?

B. When the first bump was felt was the rudder unshipped and did the International thereby become unmanageable?

C. Were all or any of the Pilots orders disobeyed?

D. Were the master and crew justified in leaving the ship and taking to the boat when they did?

The speaker recalled the position of the International when she was boarded by Masterton. She was according to evidence two and a half miles from St Martin’s Point and about five miles from the breakwater. According to the master and mate of the International when they were first boarded they had the Hanois and breakwater lights just open. The master of the tug Assistance differed slightly from this, as he said that the Hanois was not quite ope, but the glare of the light could be seen over the rocks. This was, however, not very material. The wind was described as south and the vessel was travelling at from three to four knots an hour. The breeze was described as a “commanding” breeze and a “good working” breeze for a small vessel. Taking all the evidence it was clear that it was a steady breeze, and all ere agreed within a point or two that it was blowing from the same quarter the whole evening. The learned counsel for the defence had admitted that there was error of judgement soon after Masterton got aboard in shortening sail and taking in the mainsail and stowing it, and that the error led to the vessel being found where she was. Error of judgement was not negligence or want of skill in the legal sense. The Court must decide if it were more than that admitted by the accused himself. Was it want of skill required for such a vessel as the International to be allowed to go where she was. The Pilot never expected to find himself in that position. He was more astonished than anyone to find himself where he was. There was evidence that when Masterton boarded the vessel her head was so pointed that the breakwater light was on his starboard bow. The Court would have to decide if it was the right direction or not with the tide running as it was. The ship steering for St Peter Port was bound to avoid the eastern drift of the tide as much as possible. The master of the International had said in his evidence that the pilot immediately changed his course instead of keeping the breakwater light on the starboard side, he changed and had it on the port bow. It was scarcely necessary to say if that was wrong or not. The learned counsel for the defence had said that “It would be a mad thing to do.” Anyhow, Masterton got where he should never have got and the effect was to bring the vessel in the very position which was described as a “mad” position. The error of judgement was in taking in the main-sail and shortening sail too soon. At first the vessel was thought to be travelling rather fast for the boat to be safely lowered, therefore what was the surprise of the master. Mate and Pilot when they saw a dark object which turned out to be a buoy on the port beam of the vessel. Finding himself there, the second question presented itself. Was he guilty of want of skill or negligence in casting the anchor at the moment. The Jurats would answer that perhaps in consequence of Captain Jones evidence just given or in consequence of their own convictions. It, however, turned out not to be a safe anchorage. The vessel should have been given more sail and gone on the starboard tack. Capt Jones thought it was not prudent to drop anchor where she was fund. True, 30 fathoms of chain were let out before the anchor caught and the anchorage was good enough for the time, but later the anchor dragged and the vessel was noticed by the master to be drifting although the Pilot said she was not. She again held fast and remained as described “snug” as the Assistance found her. When the anchor was dropped it was about 8 o’clock and it was not high tide until 9.10. A vessel anchored in a certain depth of water would not hold in deeper water. That was a question which seemed to appeal to the Pilot as he wished to heave anchor and sail away, but the master persuaded him to remain at anchor a little longer. The tide had risen and been on the fall two hours at about 11.30 when the Pilot was again eager to heave anchor and be off, but again the master was reluctant and pressed him to wait for a stronger tide. Why was that? The Pilots reason for wishing to go was that it was easier to sail in deep water than in swallow water, and the mater’s reason for wishing to remain at anchor was to allow the western tide to set in. At 11.30 or thereabout the order was given by the Pilot to heave up the anchor, and about five fathoms of chain had been hauled in when a beacon was noticed about a length astern. At 12,30 the Pilot was again inclined to move, but the master was still in favour of remaining at anchor because he found that although the S W tide had set in the vessels head was to leeward of the anchor and the tide was not sufficiently strong to counteract the wind and get clear of the rocks. After waiting for another quarter of a hour more chain was being taken in when a bump was felt on the keel of the vessel. The mate informed the Pilot of this and told him the rudder was unshipped. The Court must consider if there was any improbability of this. The master and mate claimed that they saw the rudder was unshipped by looking down the rudder trunk. The order was given for the anchor to be shipped. This was immediately done and everything possible was done to back the vessel out by working the starboard braces and port braces and try and work the vessel without using the rudder. All efforts, however, proved fruitless as the vessel would not pay off. A sailor who was attending to a sail aloft came down and refused to go up again. The Captain said the vessel was done for and the crew all took to the boat. The vessel was unmanageable and she did not settle on the Musée, but drifted towards the Barbé, where she finally remained. The crew got in the boat before she settled on the Barbé. Should the anchor have been slipped when it was? Was the rudder unshipped? These were important questions. The master and mate declared that the rudder as unshipped, that they could see it, and that it hung by one gudgeon only. The speaker thought that if the two lower gudgeons were away the top one must also be away. The question was raised how the master and mate could see down the rudder trunk at night time. It must be remembered that the accident occurred two or three days after the spring tide on the 22nd January. It was full moon on the 18th and on the night in question the moon would have risen at about 9 o’clock. Therefore was it not possible that the master saw what he claimed to have seen by moonlight. The master went further and said he tried the rudder, but it would not move. There was no evidence to contradict the evidence of the master and mate. On the second day of the trail the Court heard the startling evidence from De Carteret, master of the Pioneer, who had been to the wreck day after day and said he could see that the rudder was not unshipped, but was in its proper position. It was thought that if that be correct it threw a lot of doubt on the evidence given by the master and mate of the International, consequently the hearing was further adjourned to give an opportunity for an official visit to be made. Captain Jones was then authorised to go to the scene of the wreck with a skilled diver who took observations as to the real state of the rudder. The diver was, as far as the speaker knew, a disinterested party, therefore there was no cause to doubt what he had said. He said the lower part of the rudder was away from the rudder post, about 5 or 6 inches. The gudgeons were intact in their places, but the two lower pintles were snapped. The upper pintle was intact. He went further, and attributed the snapping of the two lower ones to the fall of the vessel into the position in which she now lies. That on the other hand displaced the evidence of the witness De Carteret who had also seen the vessel after her fall. The question now laid between the evidence of the master and mate of the ill-fated vessel who saw the rudder unshipped and attributed it to the bump on the Musée and to that of Mr Clancey, the States diver. Were the Pilots orders disobeyed? There was no doubt that one of these was. A man who was aloft and came down when the vessel struck the Musée refused to go back again. The Court must consider if, under the circumstances, the refusal was justifiable. Another refusal or rather remonstrance was when the crew were all in the boat and the Pilot asked them to go back to the ship because he thought that he could save her. They would not do so until after she was firm on the rock. Would the return of the crew have made any difference to the vessel’s position. It may have, but it was only within the range of possibility and not probability. Sir Henry could not understand how it was those on board the Assistance thinking they saw a light steamed towards the International, and in fact came within hailing distance, but did not see the glare or signals made by the latter, the former returning under the impression that the vessel was snug and in safety. If the Court found Mr Masterton guilty of negligence or want of skill on the first question they would probably find the subsequent events were necessary sequels. The accused had been unable to address the Court himself, but he had had an able Advocate who presented the case in an admirable manner. If the Court thought it their duty to find him guilty, always pitying the young man, they must not allow sentiment to replace justice and, if necessary, severity. It must be so, because of the risk of life in consequence of the loss of a vessel.

Jurat Collas said he felt a great responsibility in this matter as the decision of the Court might be very damaging to the young man who was just starting in life. Still he, as a Jurat, had a duty to perform to the public. On the first question he thought there was want of care. On the second question the speaker hesitated. There was evidence that the anchorage was risky. It was difficult to say if there would have been any possibility of getting out of it. It was an awkward position which no doubt resulted from the first mistake. Accused was guilty of the third question, and as to the fourth the speaker thought the Pilot should not have slipped the anchor when he did. As to the rudder, fortunately the Court had had some means of getting at the truth. What the master said was to a certain extent verified, and the speaker thought it was unshipped at the time of touching the Musée. The man who was aloft was justified in refusing to go up again after the vessel had struck, and lastly Mr Collas thought the crew were justified in leaving the vessel when they did. He therefore found the accused guilty of a certain amount of negligence, but mostly want of skill.

Jurat Collings said that during the four years he had been on the Bench this was the most complicated case he had ever had to give his judgement on. There was no question as to the Pilots mistake at the outset. As to the second question, the speaker felt the best thing the Pilot could do under the circumstances was to have dropped anchor. The tug Assistance must have seen that the International was safe, otherwise the tug would have helped her out. Question three: the result of this had been what it should not have been, therefore he was guilty on that point. As to the shipping of the anchor, the Pilot should have waited for a stronger westerly tide. He doubted if the master could see that the rudder was unshipped at night time. If the rudder was unshipped the crew could not be blamed for taking to the boat when they did. Whilst finding the accused guilty of want of skill Mr Collings did not think him guilty of wilful negligence.

After making a few additional remarks H M’s Procureur asked that Masterton’s certificate be cancelled and that he pay the costs of the action. Under the circumstances he would not ask for a fine.

Advocate Randell having pleaded in mitigation the Court adopted the conclusions.

The Star

Guernsey

25th February, 1908