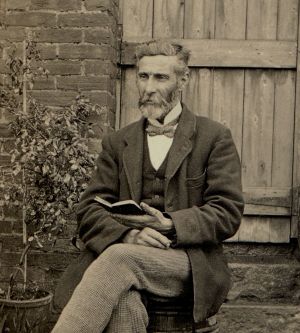

George Masterton (1850-1920)

Headmaster

George Masterton, teacher and headmaster, was born in Largo, Fife, and had a distinguished career in teaching, including headmaster of Cross Roads School, Wemyss in Fife. As well as the newspaper notices, his great grandson John Hannavy has written an account based on the discovery of his family accounts book, including the years of the Great War.

Genealogy

George Masterton was the second of eight children (seven of them boys) born to John Masterton, linen weaver, and Janet Bennett White, who had married in 1844 in Largo. George Masterton therefore belongs to the large group of Mastertons that flourished in the Largo area. He married Janet Allan in 1874 in her home town of Haddington. His son, James Allan Masterton, also became a school headmaster. Fuller details of George and his extended family can be found at this link.

Dundee Courier

Wemyss School Board – At the meeting of the School Board on Friday – Joseph Budge Esq., in the chair – the principal business was the appointment of a head master to the Cross Roads New School in the eastern district of the Parish. Out of the list of 46 applicants, the unanimous vote of the Board was in favour of Mr George Masterton, of Coaltown Colliery School, who was appointed to the office.

Dundee Courier

16th August, 1875

GRAND EVENING CONCERT.- A grand concert of vocal and instrumental music came off in the Village Hall on Saturday evening with great eclat. The programme consisted of piano duets and solos by Master James Peter, Manor House, Kirkland. The piano music was excellent, showing rich culture. The violin solo, by Mr D. Russel, Windygates, was a regular treat. The vocal part of the concert was ably sustained by Miss M. Milne, Kirkland, and Miss G. Anderson. Mr George Masterton, teacher, who is a powerful and eloquent reciter, gave two splendid recitations. Mr James McKinney was particularly at home in the rendering of his songs, and all with good taste; while Mr David Kidd and party sung some beautiful glees with fine harmony. The proceeds go to liquidate the debt on the new hall.

Dundee Courier

26th January, 1876

BIRTHS

At the Schoolhouse, Kirkland, Leven, on the 1st inst., Mrs G Masterton of a son.

Dundee Courier

5th October, 1877

Dundee Courier and Argus

A well-known personality in the teaching profession has passed away in Mr George Masterton in hs 71st year. For forty years Mr Masterton was headmaster of Crossroads School, Methil, a position from which he retired four years ago. His outstanding scholastic work was the conducting of evening mining class, quite a number of his students occupying prominent positions in the coal industry at home and abroad.

He was closely identified with the organisation of Methil Parish Church, and for many years was session clerk and superintendent of the Sunday school.

Mr Masterton is survived by a widow, two sons, and three daughters.

Dundee Courier and Argus

Monday 27 December, 1920, p7

Family History Monthly

A Schoolmaster’s Tale

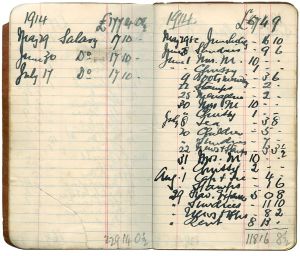

Photo-historian John Hannavy’s researches usually start with old pictures, but the discovery of his great grandfather’s family accounts book from 1913-1920 offered a fascinating insight into the cost of living almost a century ago.

Putting names to the faces which stare out at us from family photographs is one of the real challenges in compiling a family history, but simply knowing who these people were is only a small fraction of understanding where we come from – and rarely tells us very much about how they lived. If we come from middle class backgrounds, then amateur photography probably started to play a part in their lives around 1900, rather later if we are of working class heritage. The ability to afford even a simple ‘Kodak’ was initially restricted only to those for whom the five shillings’ cost of developing and printing a roll of film was affordable. By the 1920s, that cost had reduced significantly, and thus brought photography within the reach of the majority of people.

But to get a real insight into their lives, we either need to do a lot of social history research, or be blessed with the good fortune that key pieces of ephemera have survived. When a detailed account of household expenses has survived, we can learn so much more about what it was like to be alive nearly a century ago.

To paraphrase the words of Mr Micawber, “Annual income two hundred and twenty nine pounds fourteen shillings, annual expenditure one hundred and seventy eight pounds sixteen and fourpence halfpenny, result happiness!”

The 1914 household accounts of George Masterton, a school headmaster from Crossroads near Methil in Fife – and my great-grandfather – show just such a balance sheet. With today’s inflated salaries and currency values, it is something of a surprise to be confronted by detailed accounts which show that a schoolmaster and his family could live, and live well, on that sort of income. Of George and his wife Janet’s seven children, four had long since left home by that time, and had been successfully seen through university and launched on careers of their own. Chrissie – my great aunt – had stayed at home and kept house for her parents. So, in 1914, George’s salary supported three of them in the rented schoolhouse which cost £8.13s (£8.65) per annum – up from £8 in 1913.

Income tax was ninepence (just over 4p) in the pound for those earning less than one thousand pounds! The tax threshold must have been relatively high as George’s income tax bill, which he paid separately and twice-yearly in March and December, amounted to only £4.10.2d (£4.51). For 1915, with a slight increase in salary, his bill was £5.6.6d (£5.32).

In addition he paid ‘County Taxes’ of £1.18.10d (£1.94) in 1914, and £1.14.4d (£1.72) in the following year. Compared with that, his subscription to the Geological Society at 25/- (£1.25) might seem a little extravagant!

The household accounts book was discovered after Chrissie’s death, amongst papers in her house in Lundin Links, and kept for sentimental reasons by my late mother. It covers a period from July 1913 until George’s death in early December 1920. His last entry, on November 30th 1920, recorded that he had paid the newspaper bill of 5/4d. He had retired from teaching four years earlier in the summer of 1916, on an annual pension of £103.11.7d.

Life in Crossroads in those days was dominated by coal. This was the heart of the Fife coalfield and Methil was undoubtedly Scotland’s major coal port. So it is hardly surprising that one of the first charitable donations in George’s accounts, five shillings in November 1913, was to the Welsh Disaster Fund. The fund had been set up to raise money for the dependants of the 439 men who died at the Universal Colliery in Sengenhydd, Glamorgan, on October 4th.

The schoolmaster was a respected local figure, with a social status in the community that any teacher today could never even dream of. He was looked up to, and expected to maintain standards of behaviour, of lifestyle and appearance.

In the accounts book, Janet, is referred to as “Mrs M.” in each monthly entry as he recorded passing over £10 of his £17.10s salary to cover household expenses. She remained “Mrs M.” until mid 1917, when the entry changed to “Household”.

Chrissie, who acted as housekeeper, is recorded as having received one pound per month from her father. The exception was July or August when they had their annual holiday, when she was given an extra pound, and Mrs M an extra four!

At a time when the world was building up to global conflict, it is reassuring to read that in Crossroads, the burning issues in George Masterton’s life remained at a mundane level. While the Balkans erupted prompting the outbreak of the First World War, the Mastertons were concerned with the 8/8d due for newspapers, meeting the 3/6d bill for having some boots repaired, closing up the schoolhouse for the summer, and meeting the £5.0.8d travelling expenses for their annual holiday.

Despite raging inflation brought about by the million pounds a day (rising to three million) cost of the war, George’s salary increased only marginally, and the amount given to Janet and Chrissie remained largely the same until well after his retirement in 1916. By 1918, Janet was actually running the house on less than she had been given four years earlier, and the family was living in rented accommodation in Lundin Links, at a cost of £15 per annum – almost twice the cost of Crossroads Schoolhouse – their removal expenses from Crossroads having cost £5.7.6d! Inflation in the first year of the war stood at 25%, and by late 1918, prices were generally three times what they had been in 1914. Prices rising at that rate puts our own experience from the 1970s in perspective – but then salaries were rising just as fast if not faster than inflation. In wartime, wage levels were held down by government edict, as the nation slipped deeper into debt.

George did his bit for the war effort, giving generously to appeals, and becoming an assiduous saver. In March 1915 he gave five shillings to a fund to buy socks for soldiers, and in May the same amount to the ‘Belgian Fund’, half a crown to the Serbian Appeal and half a crown to the Polish Day Appeal. In June, he donated one pound to the Wemyss Soldiers Appeal. In a three month period he gave 35/- (£1.75) to war flag days from his £17.10s (£17.50) per month.

In August 1915 he invested £10 in ‘War Loans’, and in the following year, £67.8.6d in War Savings Certificates – 30% of his salary and pension! In 1917 he invested £96.17.6d in more savings certificates, equivalent to 90% of his pension, while the family lived off the income from maturing annuities and investments. War Savings Certificates – the forerunner of National Savings – were newly introduced in 1916 as an additional means of raising funds to pay for the war effort, so he must have been one of the first to subscribe to the new savings movement.

Everyday items of expenditure are meticulously noted in the accounts book, and some of them are surprisingly high! For example in the month of March 1914, he spend 2/6d on stamps –when posting a letter cost one penny and a postcard a halfpenny. That’s an average of one letter or two postcards per day!

Clothes were expected to last. Over the period chronicled within the accounts book, George certainly did not splash out! There are only a few entries detailing his clothing purchases, and none for either ‘Mrs M’ or Chrissie – so perhaps they clothed themselves out of the housekeeping. Btewwen 1914 and 1916, only four purchases of new clothes are recorded – two from Forsyth & Company in Edinburgh amounting to £5.1.6d (£5.07) in 1914, and the other for £1.10.0d two years later. In between we know he spent 4/6d on a new cap and tie, £3 for a new overcoat, and £1.7.0d for a new pair of boots – up from £1.4s in 1913. There were numerous bills for boot repair, each amounting to about 3/6d (17p). Those boots would have been well and truly worn down before they were replaced.

When George’s suit perhaps started to look a little faded by May 1919, he paid 6/6d to have it dyed – thus getting a bit more use out of it.

The very first entry in the book – in late June 1913 – records that the sum of £2.10s (£2.50) was paid to the family dentist, while in the following months, rail fares for the family holiday cost a massive £3.19.6d – much more than the £2.4.3d for a month’s rental of the holiday home. The following year, holiday travelling expenses exceeded £5!

A new pair of spectacles cost £1.10s in 1914 and £1.12.3d four years later, while a pair of ‘eyeglasses’ in the following year cost only 15/-! Amazingly, a second pair of eyeglasses in 1916 cost half that – at 7/6 they were 6d cheaper than George’s new umbrella!

While the family lived in the Crossroads schoolhouse, they do not seem to have paid utility or fuel bills – the £8.13.0d annual rent seems to have included gas, water and coal as they are noticeable by their absence from the accounts book – but once they were in Lundin Links, the family expenditure increased by about 26/- a year for gas, and 17/6 for water, while a ton of coal cost just under thirty shillings. One ton seems to have lasted them all winter, so they were either blessed with warm winters, or lived in a very cold house – probably the latter! By 1920 coal had risen by 50% to £2.12.6d a ton!

Talking to family members over the years, my great-grandfather was remembered as something of a bibliophile who perhaps spent too much money on books. If that is the case, his accounts do not really confirm it. He spent just over two pounds on books in 1914, 17/6 in 1915, only 4/9 in 1916, and 21s10d in 1917. What comes through the whole book is a picture of a man who was careful with his money, but who could be very generous when called upon to be so.

George’s son James, my grandfather, followed his father into teaching, himself becoming headmaster of several Fife schools, and also becoming the author of several of the mathematics and English text books used by generations of children in Scottish schools. The royalties from his ‘best seller’ – For Silent Reading – which remained in print from the mid 1920s through to the late 1950s, helped pay to put his children, my mother amongst them, through school, college and university.

In the late 1960s, in Bolton Lancashire, I got talking to a policeman – then nearing retirement – who had been one of his pupils in West Wemyss. “When you did something wrong”, he said, “Mr Masterton could give you a fair belting”, and then as an afterthought, added “so is Jean your mother” She was a bonny lass”. It’s a very small world.

A shorter version of this article previously appeared in Family History Monthly

Text and pictures © John Hannavy Picture Collection.