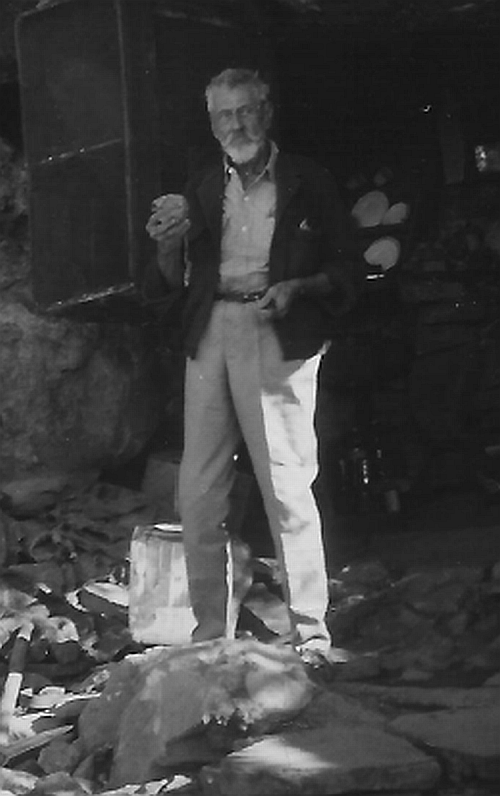

William Robert Masterton (1872-1961)

Photo courtesy of Mark Upton

The "Great White Hermit"

William Robert Masterton, after an early career as a commercial traveller, settled in a remote part of Northern Territories, Australia close to the border with Queensland, and remained there, living in a cave, and staking claims to copper deposits mined by his workforce of native Australians. He was a sportsman in his youth, being the New South Wales long jump champion, but some reported accounts of him being an Olympic gold medallist would seem to be an example of the hyperbole that can often be attached to eccentrics.

Genealogy

William Robert Masterton was the third child and eldest son of William Masterton, farmer, and Christina Dunn Forbes, who had married in 1868 in Edinburgh then emigrated to New Zealand, later relocating to Australia. He was the elder brother of Henry John Watson Masterton, who became Managing Director of s shipping company. This places him as part of the extensive family of Mastertons from Cramond for which details can be found at this link.

The Courier-Mail

Redbank Mine May Be Re-opened

An effort is to be made to re-open the Redbank copper mine at Wollogorong, near Burketown, in the Gulf country. In a letter to Mr J. E. Burke (managing director of the shipping firm of John Burke, Ltd.), the owner of the mine (Mr. W. R. Masterton) stated that he had held on to the mine for years, always believing that copper would go up in price. He had been unable to work the mine owing to the low price ruling for copper, and also because of lack of transport to the coast. In 1935 he got 80 odd tons of ore away, out of 100 mined. The ore assayed on the average 35 per cent, copper. A carrier had arranged to cart 100 tons of ore from the mine last year, but he did not arrive, with the result that Mr. Masterton had 160 tons of ore, which at the price then ruling at Chillagoe was worth over £4000. Had his ore been delivered at Chillagoe he would have had 200 tons more this year, and he would have been in a position to employ more miners at Redbank.

There were only seven months each year when it was possible to cart the ore to Burketown for shipment to Chillagoe. Mr. Masterton asked Mr. Burke to make inquiries regarding the purchase and transport of a motor truck to Burketown.

Mr. Burke said yesterday that he had seen the Under Secretary to the Minister for Mines, and was forwarding to him a copy of Mr. Masterton's letter. The Mines Department desired Mr. Masterton to forward a sample of the ore he had sent to Chillagoe, and probably a truck would be sent to him by the first ship available.

The Courier-Mail

Brisbane

Wednesday, 14th April 1937

Townsville Daily Bulletin

Important Inspection.

BURKETOWN. June 14.

Mr. Keast, manager of the Broken Hill Co., Pty., Ltd., and a party of other mining personalities flew to Burketown on June 8 in the Lockheed monoplane Silver City, which is the property of the Broken Hill Co. Mrs Keast accompanied the party to the Redbank copper mine, and expressed her keen interest in the country traversed.

It is understood that the immediate object of the visit of Messrs. Keast, Morby, Claverly, Major Thyer, and other distinguished mining experts is to ascertain and report to the Federal Government on the possibilities of opening up the rich copper deposits at Redbank. Marked activity has characterised the in- vestigation of these gentlemen, and of the personnel of the geophysical and geological survey parties during recent weeks, and it is of very special moment to local residents, as well as to the Commonwealth at large, to secure such reserves of minerals as will enable the production of war materials of all kinds to proceed rapidly and progressively.

North Queensland may expect considerable development of its industrial and transport facilities, and this will inevitably lead to improved conditions throughout the North-west, whilst providing Australia with essential elements of the sinews of war. Everything, of course, depends upon the report of the experts and the subsequent decision of the Federal Government. It is realised that existing conditions are necessarily discouraging to mining development, but a long range expansion policy may be envisaged. If this is the case the reported up to 40 per cent, assay of the Redbank copper deposits is a factor which may weigh heavily with Canberra.

Mr. Reg Murray, one time of Herberton, but now in Townsville, states that the Redbank copper field is situated about 150 miles from Burketown, just across the Territory border. W. R. Masterton, who has worked the original leases for about 30 years, went there originally about 1909 with a party from Irvinebank. They travelled overland to Burketown, where they purchased a waggon and set off with supplies. The syndicate gradually broke up until Masterton remained alone to continue working. The field is on broken, sandy country with poor road access and of late years leases adjacent to those owned by Masterton have been worked spasmodically by the Atkinson brothers, Jim and Del.

Masterton at times employs additional white labor, but uses aborigines to a large extent He has no machinery, the ore being lifted by windlass, bagged and conveyed to Massacre Inlet, in the Gulf, where it is picked up regularly each month by the small John Burke schooner Leisha, which tranships to the Wandana, by which it is conveyed to Cairns and finally railed to Chlllagoe. Massacre Inlet is about 60 miles from the Redbank field and carriers convey Masterton's ore on contract over a very rough bush road. Mr. Murray says the ore is of high metal contents, and he thinks Masterton has made enough by his own crude methods to get out. For years his abode has been in a natural cave on one of the cliff faces. The field was recently surveyed by the aerial geophysical party and a land party is now completing its investigations.

Townsville Daily Bulletin

Queensland

Thursday, 20th June 1940

Conveyor

IN May of this year Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Keast and Mr. M. Mawby made a trip into the Northern Territory per medium of the "Silver City" and then along country roads 200 miles to the Redbank Copper Mines about twenty miles across the western border of Queensland. The first 1,000 miles was traversed by 'plane in five hours, the next 200 miles took two strenuous days travelling by car. The whole story of this trip will be the subject of an article in a future "Conveyor."

At Redbank, the party met an unusual personage in Mr. Wm. Masterton, owner of the mines. Mr. Masterton is 70 years of age, and he has lived alone at Redbank, except for native help, for over twenty years without at any time returning to the outside world. During that time, with the aid of aborigines, he has mined copper ore continuously and shipped it to the most suitable market. He has established a home in a magnificent cave in the sandstone escarpment of one of the many valleys on his property from which he can look out over the thickly timbered country.

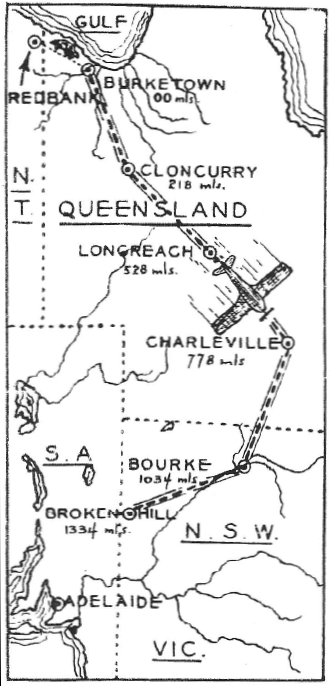

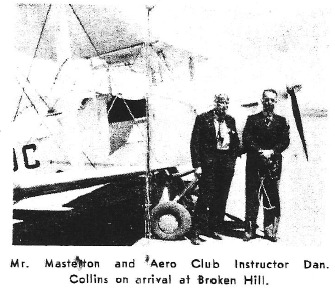

Mr. Masterton decided to return the visit, and to enable him to do this the good offices of Dan. Collins were solicited, and by leaving Broken Hill on Monday at 2 p.m. in a "Moth" plane, Dan was able to return with his passenger at 8.30 on Thursday morning. The details of the trip show that Dan reached Cunnamulla, Queensland, 443 miles, by nightfall, and leaving at daylight he arrived at Burketown, a further 891 miles, by 6 p.m. On the following morning (Wednesday), with Mr. Masterton as passenger, the 'plane left Burketown at 5.30 a.m., and after refuelling at Cloncurry, Longreach, and Charleville, arrived at Bourke at 6.45 p.m. The day's flight covered 1,034 miles, and this is believed to be a light 'plane record. The departure from Bourke was made at 4.45 a.m. on Thursday, and Broken Hill, 300 miles distant, was reached by 8.30 a.m. Thus all flying was completed in daylight and the distance of 2,668 miles covered in 30.55 hours, an average flying speed of 89 m.p.h.

This was not only Mr. Masterton's first flight, but it was also the first time he had seen an aeroplane. He took a keen interest in the flight, and expressed the opinion that it was like riding in an armchair.

Conveyor

Zinc Corporation

December 1940

Northern Standard

MINING ORDINANCE 1939

NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A MINERAL LEASE

NOTICE is hereby given that I William Robert Masterton of Wollogorang Station the undersigned, has made applications this day for a Mineral lease under the provisions of the Mining Ordinance 1939, of ground to be known as The "Bluff" containing twenty acres situated at Redbank via Wollogorang and commencing about 2 miles easterly from Redbank Mine from datum peg West; running north of east for twenty chain then south-easterly for ten chains, thence south-westerly for 20 chains, thence north westerly for 10 chains to datum peg. Includes former Protected Mineral Lease 1281.

Dated at Redbank this Twenty-fourth day of December 1940.

Signature of Applicants or Agents

WILLIAM ROBERT MASTERTON.

OBJECTIONS to the application above referred to must be lodged at the Warden's Office on or before the 24th day of February 1941, and the hearing of the application will take place on the 18th day of March next.

C. R. STAHL,

Mining Registrar. McArthur River Gold-field.

Northern Standard

Darwin

Wednesday, 29th January 1941

Report on the Borroloola Mining and Cattle Districts 1948

6. Redbank Copper Mine

Owner - Mr W Masterton, aged 77 years

Mr Masterton has been in this area since 1900 and has continually worked the copper mine throughout this period. He lives in a very primitive condition, his quarters being located in a cave. At the time of my inspection Mr Masterton had no natives in his employ. His last aboriginal licence was held in 1945. He stated he had not worked any natives since that date.

Mr Masterton's copper mine has been inspected by engineers and assayists from the Zinc Corporation, Broken Hill. He told me that they had reported that there was insufficient ore in the area to warrant a large company taking control and erecting a smelter.

There is no doubt that the Redbank mine could be a successful one now if the owner had sufficient capital to become modernistic, ie, own a motor truck, pump for sluices, etc.

The isolation of the mine is the greatest handicap to overcome especially as all the ore has to be shipped to Newcastle, NSW.

Living near Masterton were the following natives :-

| Relation | Name | Native Name |

| Husband | Old Tommy | Yed-ud-era |

| Wife | Judy | Kak-a-la |

| Wife | Bella | Oong-oona-mura |

Living with Mr Masterton in a cave adjoining his was a young half-caste girl named Florine. This girl's age was 16 years, her mother was the above lubra, Bella. As far as could be ascertained her father's name was Mr Holmes, address unknown.

Masterton stated that he had taken this half-caste girl from the native camp at an early age and had looked after her interests ever since. He had given her a little education, clothed and fed her. He requested that I remove the girl as the residents of the various stations and people in Burketown claimed that he was living with the girl. I assured Mr Masterton that the girl would be removed in the very near future but it was quite impossible for me to take her with me on patrol as I had over 200 miles to ride to Borroloola. I questioned Masterton with regard to various rumours I had heard with reference to the girl Florina working underground. in one of the mines.

He admitted that she had been underground but claimed she had only gone down for the adventure and unknown to him at the time. He stated that he had reprimanded her for doing this and claimed that the community was only trying to give him a bad time. I am quite convinced that in the past Masterton has acted in the best interests of the girl.

Also in the Redbank area were the following natives :-

| Relation | Name | Native Name |

| Husband | Charlie | Yal-ar-al |

| Three wives | Maudie | Pumyal-border |

| Mollie | Jaya-lla-bina | |

| Violet | Kydee-bba | |

| Daughter | Maggie | Mun-galli |

The following half-castes were living in an iron shack known as Shadford's camp. This house is owned by Jack Shadford.

Phyllis Shadford H/C, aged 7 years

May Shadford had a daughter Doreen aged 7 years, also a daughter 4 weeks old, both quarter-caste children.

The father of the second daughter is unknown. The name of the father of Doreen was alleged to be a stockman by the name of Billy Cain whose present address is Stapleton Station. Billy Cain has not a good reputation, he was arrested and charged with cohabiting, found guilty and served six months in Alice Springs Gaol.

I consider that Cain should be approached and questioned as to whether he is the father of Doreen. As he has already served a sentence for cohabiting there is the possibility he may admit to being the father.

In the event of this happening he could then be made to pay an amount each week for the upkeep of the child.

The Shadford girls were living on rations that their father had sent up from Wollogorang Station.

Report Relative to Mines and Cattle Stations Employing Native Labour in the Borroloola District

S H Kyle-Little

Patrol Officer

National Archives of Australia, Darwin Office

CRS F315/0 Item 1949/393A Part 2

16 December 1948

The West Australian

DARWIN, April 25: The Northern Territory is already at the polls voting for a man who will not have a vote except on parochial issues.

The electorate, which covers 523,000 square miles and 14 degrees of latitude, has only three polling places - at Darwin, Tennant Creek and Alice Springs - for 6,556 electors. That is an average of one polling booth for 174,000 square miles or a place twice as big as Victoria. About one-third of the electors have already recorded their votes by post in what is believed to be the biggest percentage of postal votes of any electorate. The Electoral Officer (Mr. J. W. Nicholls) sent ballot papers by aeroplane and native runner to most inaccessible corners of the country as soon as they were printed. Many of them have already come back with votes marked but some will not have yet reached their destination. Mr. Nicholls. who has 26 official positions in the Territory, has conducted every election here since 1928. A voteless Territory native will walk out 100 miles with the ballot paper for Mr. W. R. Masterton, the miner at the Red Bank Copper Mines, Wollongorang, wait until he marks it, and then walk back. On his way out the native will have to swim the McArthur, Wearyan, Robinson and Calvert Rivers and Skeleton Creek, all of them populated with crocodiles. He will swim them again on the way home.

The West Australian

Perth

Thursday, 26th April 1951

Townsville Daily Bulletin

(By "SUNDOWNER")

T.H.C. takes his place at the campfire again this week, with more to tell us about his experiences back in 1909:

When we camped at Almaden, on my way from Chillagoe to Einasleigh, I met an exceptional type of a man named Masterton. He was a Gippsland native. A clean, natty man, his swag consisted of one change of clothes and a calico bag the length of his swag that he used to keep filled with flour when he was on the track. He told me he had walked from Mungana to Port Darwin, then to Derby and Marble Bar in West Australia, and now he was returning and going south. He told me his reason for coming back this way was that there were too many long dry stages on the Overland Telegraph Line from Darwin to Adelaide, otherwise he would have taken that route instead of following the Gulf around. Masterton was a most interesting character and could converse on any subject. I mentioned to him that seeing he was that fond of travel it was a wonder he had not got on with a mob of cattle. He replied 'I would not get on a horse if you gave me £10.'

Townsville Daily Bulletin

Queensland

Monday, 18th August 1952

Townsville Daily Bulletin

(By "SUNDOWNER")

Mr. H. H. Macintosh, Fairfield, Longreach, writes :— Your correspondent T.H.C. (August 18th issue) mentions a man named Masterton— 'an exceptional type of man' etc., whom he met at Almaden In 1909. I have no doubt he will be interested to know that W. R. Masterton, the same man, has a copper mine in Wollogorang, N.T., not far over the border from Queensland. I first met him there in 1915, living under an overhanging rock face, and he is still there. He is about 79 years of age, and he is still 'neat and natty.' and active, an athlete in his younger days, and as T.H.C. said, can converse on many interesting subjects.

Townsville Daily Bulletin

Queensland

Friday, 12th December 1952

The Sunday Mail

THE WHITE HERMIT of the RED BANK MINE

By DICK WARDLEY

BACK from the turn of the century he was a champion New South Wales athlete with "the strongest legs in Sydney."

BACK from the turn of the century he was a champion New South Wales athlete with "the strongest legs in Sydney."

Now he is a caveman in one of the wildest corners of the Northern Territory and "nobody" he was to say to me, "wants to listen to a failure." But he has not failed because he is a rare man, a unique Australian and, at 87, the last of our true frontiersmen. In Burketown, North Queensland, on the southern lip of the Gulf of Carpentaria, where the coming-in and going-out of the tide is like the rise and fall of a giant's chest, they had called him "The Great White Hermit."

And 300 miles back the way I'd come, at Mount Isa, a bearded prospector in from the Gulf, had said: "I never saw him. But I heard he lives in a cave like a ruddy Robinson Crusoe, with a team of niggers his Men Fridays. Away to blazes in there by the Big Calvert, somewhere."

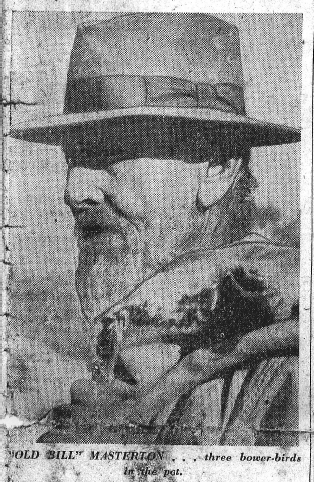

They called him "Old Bill" Masterton, and few had ever seen him.

In fact, it wasn't until I reached a remote uranium camp named Milestone, a small tin-and-canvas oasis by Settlement Creek, south-east of Massacre Inlet, out through Domadgee Mission, and 175 miles south-west of Burketown, that I encountered anyone who had met him.

There, a young Queensland geologist, Rick Campi, said he had met the hermit; an American, Mike McGrath, at Milestone to report on minerals for the Atlas Corporation of the United States, had seen him, too.

"A rare old guy," drawled McGrath, "and the Lord alone knows how long he's been living in there. His claims are all over the map in those parts. We were up in that country, and went in for a look-see at his mine. I recall him saying "Gentlemen, you'll stay for supper, although all I have to offer are those three bower birds in the pot."

Campi said: "We could go that way to-morrow." We included the two geologists, myself, and earthmover Don Rosewall, to whom the geologists were to show a manganese deposit near the Big Calvert River, in the west. Red Bank Mine was about 100 miles that way.

The way was through bull-dust deeper than the tyres of the jeeps, and across dry river beds, of rocks and stones, thirsty for the coming wet; high grass where snakes curled; over wide, fawn plains, where kangaroos abounded and the wild turkey clattered up across the bonnet. It was a lonely belt of blackfellow country where there lived but one white man; Masterton, of Red Bank Creek.

We came on the clearing suddenly, late in the tropic day; a muster of lean-to's and woodbark huts with nothing moving. People stood there, not moving, just waiting, watching. There was the smoke of their fires, purple in the glade, with the smell of kangaroo meat; fresh and wet, dripping after a hunt.

Campi came back to say: "He's down the mine." He stood on a hill of ore by an old rusted windlass above a shaft, one of several on the mine. Straight as a spear he was with a goatee beard, a tall old man clad in khaki shirt, pants, brown boots, and a beaten-up old hat over keen blue eyes. Nimbly he walked as he came down the copper hill.

Hands shook all round and then he began talking copper. I watched him collect a chunk of pinky-green chalk-like ore from the hill of copper oxide. This ore was taken fron the shafts by Masterton and his dark helpers, mostly lubras, whom he called "the girls," and bagged for transport, whenever such passed through that corner of the nowhere to Burketown to be shipped to Port Kembla. So practised is the old man that, by now, his judgment of the ore by eye alone is never more than one per cent out.

I walked to a shaft and dropped a stone, listening for it to fall, and his voice when he spoke came from a time when English WAS spoken: "That shaft I haven't worked for 21 years." "How long have you been here, alone like this?" "Since 1913." "Have you been away at all?" "I went back to Sydney, yes," he said, "when my wife died, and my son Henry, in the war." "When was that?" "1919," he said, as if it was yesterday, and not 38 years ago.

I asked Masterton if he would pose with the blacks for a picture, but with finality, and yet with dignity, too, he refused. He was king here. Most of the natives he had known from the day they were born. Not all of the "20 head" worked for him, but he provided them all with tucker, tobacco, and the clothing he saw they wore. Once, long ago, a native called "Murdering Tommy" had unsuccessfully tried to kill him. When he didn't repay in kind, it was the natives who saw that Tommy "went away," an outcast forever.

Huge mango trees grew by a creek bed near an old garden, spiked off with a corral of bamboo, and when you walked past the trees you stepped back two thousand years. Here lived the cave man.

And here, like a page from the Bible, was a woman carrying water from a spring - the sweetest water you could ever taste - and carrying it with a wooden harness across her shoulders and a pitcher on either side. She was the "girl" of the day, who prepared the master's table and cared for his cave. It was about 12ft high at the entrance, and tapered down into the face of solid rock for about 20ft. It had a veranda of natural stone on which stood two chairs made of bag and bush timber. Just below was the kitchen, with a bush fireplace.

In the cave was an old bed, old books, and all manner of bric-a-brac, a sort of cameo of the hermit's time as a castaway from civilisation - an old pocket watch, which had stopped, hung on the stone wall near three ancient guns; a wire safe, a wooden table, tin trunks which he had fetched with him from Sydney so long ago; a miner's pick, and a triangle made from a rusted collar which had belonged to either a horse or a bullock.

There was tea, sugar, and flour in bags, and now a brew the black "girl" brought. "What brought you all the way to this place?" I asked.

"I came here," he said, "to look for copper. I had people behind me in those days with plenty of money." He paused, sipped the hot tea, looked out at the branches of the green tree, and at something else only he could see. "But the depression killed all the people."

"What did you do before, in Sydney?" "I was a commercial traveller," he said. "Someone told us you were a pretty good athlete in your day," Don Rosewall said. "The old man had kept some papers. I wondered how often he had read them down the lost years. They were dated in the 1890's when he was broad jump champion of N.S.W. The now defunct "Referee" said of him: "Masterton had the strongest legs of his day in Sydney." He represented N.S.W. in New Zealand in 1896.

"How are things," he said to Campi, "down at Milestone?" "We're moving out," said Campi, "before the wet." The old man did not speak for a moment. "Oh," he said, "you are leaving." I said; "Do you expect to go south again?"

That would cost money." He looked away and his eyes came back. "And besides how could I leave all this, just leave it here?"

"I would like to go back," he said. "Yes, I know Sydney so well." So well, I thought, and the trams banging, the taxis, the neons, the shops, the high buildings, the radios, the television, the artificial heating, the dress, the noise, the pace, and a thousand things you have never seen.

The Sunday Mail

Australia

27th October, 1957

Sydney Morning Herald

DARWIN, Thursday.- Old Bill Masterton, 91, the "Great White Hermit" of the Northern Territory, is dead.

Word of his death several weeks ago in the remote Gulf of Carpentaria district reached here today. He had lived in a cave at Red Bank copper mine, near Wollogorong Station, on the N.T. Qld border for 48 years.

He had been south to Sydney only once in that time - in 1919 when his wife died.

Few men ever saw him, although he was a legend in the country.

Natives of the Garawa tribe helped him work his mine. When he had a load, a carrier called and carted it to Burketown for shipment. He had to handpick his ore for grade.

Once, years ago, a native named "Murdering Tommy" tried to kill him. When he failed, and when Masterton repaid the attack only with kindness, the other natives saw to it that Tommy "went away." He lived on wild game hunted by the natives, who treated him like a king. The natives buried him at the entrance to his cave.

Shortly before his death an aboriginal woman named Laura spoke of the tribal life with Masterton. "He is a good man," she said. "He has looked after 20 of us for many years. "There is never any trouble."

His cave on the side of a hill, was 12 feet high at the entrance, 20 feet deep, and had a veranda of natural stone. His chairs were made of bag and bush timber. A native woman swept it out each day and set the table at meal times.

Mrs A.J. Keast, of Monomeath Ave., Canterbury, Victoria, wife of the managing director of Mary Kathleen Uranium, visited Masterton with her husband recently. She said: "He was one of the most gentlemanly men I ever met. "In his cave at dinner time, he said to me, "Madam would you kindly serve" - he hadn't forgotten the woman's privilege."

Masterton was once broadjump champion of N.S.W.

Sydney Morning Herald

22nd July, 1961 (probable date)

The Age

DARWIN, Thursday. - Ninety-one-year-old Bill Masterton, who lived in a cave at Red Bank copper mine on the Queensland-Northern Territory border for 48 years, has died.

He is known throughout the Territory as the "Great White Hermit." Word of Mr Masterton's death several weeks ago reached Darwin today. He lived in the remote Gulf of Carpentaria district in a cave near Wollogorang Station. His only visit south was to Sydney in 1919 when his wife died. Few people ever saw him, but he was a legend in a country of legends.

Only a four-wheel drive vehicle and tough stock ponies could get to his cave-mine. But Mr. Masterton had neither. He employed 20 natives of the Garawa tribe to help him work the mine, and when he had a load of copper a carrier called and carted it to Burketown for shipment to a southern smelter.

Because of the vast distances to be covered he hand to hand-pick his ore for grade. Aboriginal women carried his water in buckets on a yoke from Red Bank Creek. Natives at Borroloola, 100 miles away, say that Mr. Masterton was the good man who looked after many natives for years.

His cave on the side of a hill was 12 feet high at the entrance and 20 feet deep. It had a verandah of natural stone. His chairs were made of bags and bush timber and a native woman swept it every day. He lived on wild life, including bower birds.

Mrs. A. J. Keast, of Monomeath Avenue, Canterbury, Victoria, wife of the managing director of Mary Kathleen mine, visited Mr. Masterton with her husband some time ago. She said later he was one of the most gentlemanly men she had ever met. In his cave at dinner time he had said: "Madam, would you kindly serve." He had not forgotten the woman's privilege.

Mr. Masterton was a commercial traveller in Sydney last century and in the '90's was broadjump champion of N.S.W. But he gave the city away and headed for the bush where the mailman called once every three months.

Chief mourners for Mr. Masterton are surviving members of the Garawa tribe who will regularly visit his outback grave.

The Age

Melbourne

Friday, 11th August 1961

Bill and his cave

This picture - one of the few ever taken of Masterton - was snapped outside a store-room near his cave by Darwin policeman Sergeant Bill Taylor. Sgt. Taylor and his family visited the caveman just before his death several months ago. It was taken on a color film and sent south to be turned black and white for reproduction.

Masterton, 91, lived for 48 years in his cave at Red Bank copper mine near Wollogorang Station on the Northern Territory - Queensland border. A "true friend" of the natives in the district, he aided them wherever possible throughout his life and they helped him to work his copper mine.

Recently Masterton staggered as he finished work for the day and collapsed. Natives went to his aid but he died soon afterwards. His native friends buried him near the beloved cave and were the only mourners at his funeral.

TENDERS are called, closing at office of undersigned at noon on April 24, for purchase from estate William Robert Masterton, deceased, of whole interest in copper Mineral Lease 6C of 20 acres known as "Redbank" and half interest manganese Mineral Leases 17C and 18C of 40 acres each known as "North Calvert River Manganese" Nos. 1 and 2, and in McArthur River area. Neither highest nor any tender necessarily accepted.

WARD & KELLER, Solicitors, Chin Building, Knuckey St., Darwin.

End of a Beginning

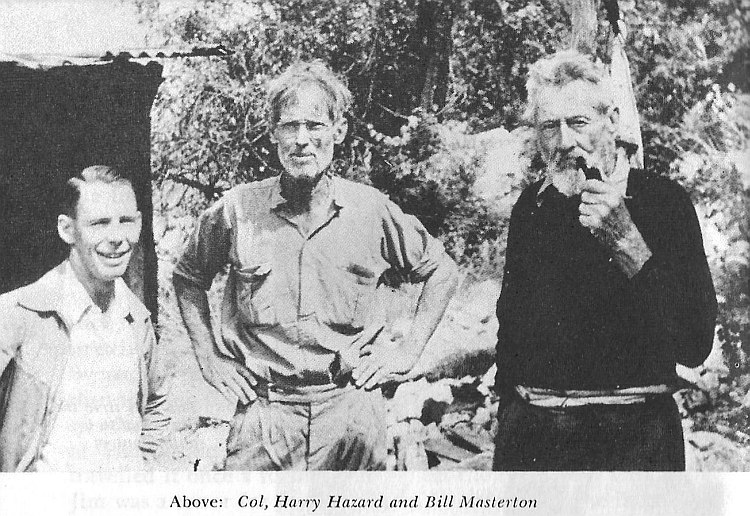

Bill and a neighbouring prospector, Harry Hazard, appear in a biographical account of one of the Australian Inland Mission padres and his wife. Their parish covered the northern third of Queensland in the late 1950's and early 1960's.

..After smoko he decided we should go and call on his 86 year old neighbour Bill Masterton who owned the Redbank mine about two miles away. Harry and Bill were quite good mates but they did not bother very much about one another so this visit was quite an occasion for him as well as for us. We were to go in his Blitz buggy. A goodly assortment of natives leaped on to the truck tray and we were both acoommodated in the cabin.

What a trip! The thing sounded like an aircraft as it was revved up, and the noise only eased off a fraction once we were under way and went careering through the scrub. Col was sitting on an upturned drum and thought he was uncomfortable. I was on the engine casing until the smell of burning moved Col to invite me to share his lap. Worst of all, I had the feeling that on this ill defined track we were missing trees by the grace of something that was not Harry's driving. It was almost as though he did not know the road and yet the breakneck speed at which we moved and the fact that he had been living there for years, assured me this could not possibly be the case. But I was not surprised when he at length bellowed out, "When your eyesight's failin', you gotta take it easy, eh? At times I can't see a bloomin' thing on this track now!" As if we didn't know.

Amazingly enough we reached our destination safely, though when we pulled up at the base of a towering rugged mountain where only two hoary mango trees suggested any trace of past habitation, it was hard to believe we were at the Redbank Mine.

"How are you at climbin', Missus?" enquired Harry.

I was reluctant to make any claims.

"You gotta be a bit of a mountain goat to visit the old man," said this young blood in his seventies.

More bewildered than ever, we silently followed him up the steep side of the mountain, wondering idly why he broke off a young sapling and took it with him as he climbed. After some time we stopped, and there he was. On a wide flat ledge, sitting in a bag chair, and reading Brisbane's "Courier Mail", was a tall well-built man with a flowing grey beard and one of the strongest and most striking faces we had ever seen. Bill!

He looked up from his paper, smiled, stood and slowly extended his hand to us in turn. Then with an old world charm, he graciously but almost nonchalantly, greeted us with, "How do you do? It is nice of you to call. Will you have a cup of tea?" as though visitors were a daily occurence. Harry was visibly exasperated by his restraint.

Bill was a mystery man indeed. He had come first to Burketown as a commercial traveller in 1910. The prospecting fever took hold of him and he found his way out to the ranges. For the past forty years he had lived the existence of a cave-man hermit, completely isolated, apart from his own tribe of natives who lived at the bottom of a hill, and of later years, Harry's mob a little distance away. The cave was a horror, composed of a deep gash in the hill and beneath a million tons of rock hanging at an angle which the geologists asserted was beyond the critical point of balance. So convinced were they of this, that when Bill invited them in for a drink, they always went in, collected it and beat a hasty retreat outside. "I wouldn't go in once, either," volunteered Harry, "but I've grown tired of life since!" I hadn't, so I did not waste time there, despite the fact that Bill insisted we explore some of the murky depths and inspect some of the cracks which were regarded as dangerous. Bill was not in the least worried. He reckoned he had been safe enough for forty years so the chances were fairly good for the rest of the time remaining to him. Anyhow, since as well as the weight of the rock he had all his gelignite stored inside, he would not have known very much about it, had it come down.

Before we went in Harry called out,

"Hey, wait on," and picking up his sapling he propped it up between the roof and the floor, saying to Bill at the same time, "Better add some reinforcement to make it safe for the padre." Bill replied softly and without a suggestion of a smile, "Oh, I don't think that will do any good."

The plan was that Bill and his mob would join us at the Prince Mine for an evening of slides, and in the meantime we would return with Harry, have another chapter of curry and turnover and then go on to Calvert Hills, the only remaining station to the west. This was a frustrating visit. It took us a couple of hours to arrive and as we were due back at sundown we barely had time to do more than say hullo. And it did not add to our ease when we discovered our hostess had beds ready on the assumption that we would spend at least one night with them. However, we felt it imperative we go back as planned, which was wise, for everyone was already assembled even when we drove in.....

...The slides were a riotous success. Bill casually announced that the last picture show he had attended had been a magic lantern show sixty years before. The natives had never seen anything like it. They howled with laughter continually through the performance. Even Harry's eyesight improved sufficiently for him to recognise familiar spots. It was by far the most unusual audience we had ever had, and certainly the most appreciative...

..The memory of our visit to Harry and Bill still rates among our prize possessions. In that short encounter they taught us a great deal. Each was a real prospector-a dinkum gambler who was in the game for the fun of the chase itself rather than the prize. They were quite content to take the bad strikes with the good without questioning and without bitterness. When you have lived like this for half a century, it is probably inevitable that your life acquires a certain serenity about it, and in their eyes the avaricious gleam of a bonanza-seeker had long since been replaced by calm acceptance of life as it came. Furthermore, they lived on the frontier of life where none of the pettiness of more closely settled areas had any place, and so we met in them a sincerity which left us standing. They were bewildered that a young couple should go where no one else had bothered to go simply in order to see them, but this did not mean they distrusted us or waited for the rub, as did so many others. They accepted it too and produced a hundred acts of childlike kindness to show their appreciation. As we left them, we shook each by the hand and I can still remember Bill's keen old eyes looking deep into mine as he said, "You will come back, won't you? You must." That's all. No flowery speech. No slick turn of phrase. Not even a lengthy attempt to articulate what was in both our hearts. And seven years of patrolling has brought no greater assurance that the game was a worthwhile one.

And by one of those strange coincidences that happen occasionally, even as I have been writing of this, word has come through of Bill's death. Harry pulled out some years ago but Bill stayed on in his cave. His dying was as lonely as his living and only some weeks after his passing, did word get through to Darwin. Few ever met him. No one really knew him. But those of us who crossed his path are unanimous in the opinion that here indeed was a man of rare quality.

End of a Beginning

Margaret Ford

from Chapter VII "The Edge of Nowhere"

pp 73-78

Hodder & Stoughton, 1963

The Redbank Hermit

W. R. Masterton was born at sea while his parents were making the voyage from Scotland to New Zealand, where they settled for a few years before moving to Australia. He was a keen athlete and won several prizes for running and high jumping. In the 1890s he was the long jump champion of N.S.W. and in 1896 he represented Australia in New Zealand. He was also a keen traveller and fisherman.

Masterton left his wife, 4 sons and 3 daughters in 1909 because the depression caused a loss of jobs. He went to Lightening Ridge to mine for opals. He sent tins of them to his wife. Many years passed in which there was no contact with his family then surprisingly one day, a letter arrived from the Gulf. He worked a copper mine at Redbank, west of Wollogorang. With the help of Aborigines and the Campbell boys from Wollogorang he bagged the copper and transported it by wagonette to Massacre Inlet. From there it went by coastal trader to a smelter. Some sources say it went to Port Kembla, others say it went to Chillagoe in Queensland. He would go by boat to Sydney, where he would visit his family briefly before returning to Redbank. His wife died in 1920 and Bill no longer visited his family.

Bill used to collect his stores when the boat called in to Massacre Inlet and get his mail from Wollogorang. Bill the Redbank Hermit, had a vision of his mine being run by a big company with many employees, a railway and a town. Mining company representatives did visit the mine and were impressed by the richness of the load. Bill's cross cut mine struck copper at 54 feet. In 1940 Mr A. J. Keast, his wife and 2 geologists of the Zinc Corporation flew to Burketown then were driven to Redbank. Keast was interested in optioning the mine. He found Bill had maintained a genteel manner and had many Aboriginal friends whom he supplied with food and clothing.

Bill lived in a cave until he died at Redbank in 1961. His vision of a large mine had never been fulfilled.

Borroloola: Isolated and Interesting, 1885-1985

J. A. Whitaker

Tropic Tide

Bill Masterton (misspelled!) makes a cameo appearance in the biography of Bruce Perkins ("VB") written by his daughter Mandaley Perkins.

"William R Masterson (sic) was the proprietor of Redbank Mine, and had been since around 1918. A former bank employee, he'd come out bush to escape the city after his only son had died in World War I, making a new life for himself out of a claim on a bit of low-grade copper in the weathering zone of a mineralised area. His home was a cool, dark cave in a piece of rocky excarpment some twenty miles west of the Queensland border. It was late in the afternoon when VB and John found him, lounging on a bush timber and sacking deck chair at the entrance to his cave. He was smoking a pipe and reading a copy of the Illustrated London News, some months old, for which he had a subscription. At eighty-something years old Masterson was no spring chicken, but he leapt out of his chair like a man half his age and welcomed his visitors heartily. Wiry and fit looking, a natty blue scarf tied rakishly around his neck, his singlet was cleanish and his white beard the neatest they'd seen in weeks. 'How do you do,' the old hermit said in a well-modulated, perfect BBC accent. His speaking voice would not have seemed out of place in the best London society and had been acquired, VB decided, from having spent forty-odd years with little company other than his radio, on which he religiously listened to the BBC World Service.

Masterson was quick to produce a billy full of strong tea. In his cave was a refrigerator box, a contraption with mosquito netting around it over which hung a dripping bucket of water. Out of it he produced what looked to John like a softly furred green rabbit. On closer inspection it proved to be a cake, homemade out of a packet, and very mildewed. 'I hope you don't mind but I added a solid dose of garlic powder to it to give it some taste,' Bill said as he handed them a plate each. They accepted politely, and though VB hardly noticed the fungus, John privately wondered at the things he would do for a company when still hoping for a career. The cave could have been tidier, VB observed, but it was serviceable and, sitting comfortably in a 'Masterson deck chair' they listened to the old man tell his story. From where they sat the view over the lowlands of the north of the Barkly Tablelands was little short of magnificent. Bill Masterson thought he had it made.

John had never seen anything quite like Redbank Mine. Though old Bill had many years experience, John soon spotted that he didn't know a lot about the business. His small shafts ran randomly in every direction, and any time he passed some ore he dug it out and sent it to Mt Isa Mines, the company which sent him his supplies and his Illustrated London News. Masterson's team consisted of himself and two Aboriginal women who stood at the top of the incline shafts turning the windlass and emptying the rawhide bags as they were winched up. Holes for the shafts he drilled with a drill rod and hammer in the most primitive way, and when they were deep enough he loaded them with dynamite and put a fuse on it. Materials had to come a long way to Redbank and Masterson didn't like to waste them. In view of this the fuses averaged about one foot in length. VB watched in amazement as the old man lit the fuses with his pipe and then scrambled out as fast as his eighty-odd years would carry him, running for safety and ducking the boulders sent flying by the explosion as he went.

The Redbank area, John assessed, was not going to make either Alcan or Masterson a fortune and, leaving the friendly hermit to his work, they headed north-west. It was now almost the end of November. There'd been a few isolated storms, but the black soil was still dry and almost rock hard. It would turn to a sticky mire after a few inches of rain, completely clogging the wheels of the vehicles.

By early December the strangers at Borroloola had moved on to spend two or three weeks looking over the southern region of the concession from a new base at Robinson River Station, seventy miles south-east of Borroloola. There the camp overlooked a dry river gully, and the four of them shared its one waterhole with a hundred species of birds and a herd of station horses. VB knew that south of Robinson lay the best cattle country in the Northern Territory, the black soil and Mitchell grass plains of the Barkly Tablelands, almost one thousand feet above sea level. He had learned not to expect much, but the vast region of dry, withered grass and hard baked ground had John reaching for his camera to photograph what passed as first-class cattle country in the Northern Territory of Australia. The folks back home in Holland would never believe it.

Three weeks on, the rain storms were becoming more frequent and it was time to move out. Supplies were running low. The last side of bacon from the Borroloola supply boat, Cora, and the last of the eggs from the local station-owner, Jack Camp, had gone.

Tropic Tide

Mandaley Perkins

pp 246-248

Bantam, 1998

The Central Australian Stolen Generations & Families Aboriginal Corporation (CASG&FAC) Link-Up team conducted reunions in Alice Springs and the gulf country around Borroloola in the last few months.

In September, the McMasters family returned to the cave from where their father was removed. Bill Masterton, known as the Redbank Hermit, lived in the cave for 45 years while he mined copper nearby with the help of local people.

The cave’s old kitchen and cot areas have been sitting unused since the Redbank Hermit died in 1961. The McMasters heard about how the old people transported copper on horseback to the coast 100km’s away. They also made contact and formed relationships with the Redbank Hermit’s European family and Redbank Operations, the mining company which manages the site.

During the trip to Robinson River and Borroloola, the McMasters family met and yarned with some of the old Garuwa and Waanyi people who were able to tell them about their grandmother and other family. They even did some fishing but being desert mob ‘the fish wouldn’t eat our beef’.

National Link-up News

Edition 13

December 2009

Redbank Copper Limited

HISTORY

Copper mineralisation at Redbank was discovered in 1916. Small scale-production between 1916 and 1957 yielded 1,200 imperial tons of copper ore at a grade higher than 30% Cu. Numerous companies investigated the area between the 1940s and early 1990s. A small open pit at the Sandy Flat deposit operated during the 1990s and processed 170,000t grading 5.4% copper, as well as leaving 54,000t grading 6.0% copper together with mining and processing infrastructure.

- 1900 Copper mines were first discovered in the district in 1900 at a resource called China Girl, 25km to the north east of the Project area.

- 1912 Further discoveries were made in 1912 at Packsaddle and Bauhinia prospects, 17km to the east of Redbank.

- 1916 Copper was initially detected in the Redbank Copper Project Area by William Masterton.

- 1916-1957 Masterton achieved small scale production from shallow open pits and shallow underground workings in the supergene copper carbonate zone at the Azurite, Redbank and Prince deposits. This total production was more than 1,200 tonnes of copper ore.

- 1966 Granville Development mined 2,000 imperial tons at a grade of 15% copper in 1966 which was sent to Mt Isa for treatment.

- 1969 A joint venture between Harbourside Oil NL and Westmoreland Minerals commenced.

- 1971 Harbourside was then joined by Newaim a consortium consisting of Newmont Australia, AMP and ANZICI. Newaim considered the discoveries which they made did not meet their corporate requirements and withdrew at the end of 1971.

- 1972 Triako Mines NL entered into an agreement with Harbourside to explore at Redbank. Harbourside withdrew. Triako continued with various partners until 1983. The project was ultimately acquired by Alameda Pty Ltd.

- 1983 An allied group of companies, Sanidine-Restech-Hunter Resources-Vanoxi took control of a much reduced area, which they protected by ERL94 and maintenance of the MLN.S. Work at Sandy Flat comprised 12 RC percussion holes to establish that diamond drilling had not downgraded the deposit by washing out the sulphide minerals. Hunter also endeavoured to characterize the deposit by further refining the work initiated by Triako using RRMIP over the Sandy Flat ore zone.

- 1989 Redbank Copper Pty Ltd purchased the tenement group from Sanidine-Vanoxi in December 1989. The final title was obtained in March 1990, since which time RCPL have undertaken two diamond core programmes to provide material for metallurgical testwork (November 1990) and to increase the resource. Cash flow analyses, market location and PER documentation followed.

- 1990 Larger scale operations were undertaken in the mid 1990.s (Amalg, 1990) when the Sandy Flat pit was developed to supply sulfidic ore to a 200,000 tonnes per annum flotation plant built at the site. Some very high grade (>25% copper) ore was also direct shipped at this time. The operation ceased after less than 2 years because of declining copper prices. With the exception of the mill, the flotation plant and crushing circuit remain on site. The most recent leaching operation began producing on an intermittent basis in 2004(Redbank Copper, 2001, 2004, 2005) and utilised oxide ore, that had been stockpiled during the mining of sulphides from the Sandy Flat Pit.

- 1995 Alameda joined by CRA Exploration Ltd in a farm in and joint venture.

- 1996 CRAE withdrew.

- 1993 Alameda Pty Ltd commenced mining a small open pit operaton 50 metres deep at the Sandy Flat deposit between 1993 and 1996 processing 170,000 tonnes at 4.6% as well as leaving 54,000 tonnes at 6.0% in stockpiles.

- 2005 Burdekin Paciific acquired the Redbank Project and changed its name to Redbank Mines Limited.

- 2008 Stirling Resources Limited acquires a major stake in Redbank Mines Limited.

- 2009 Redbank Mines Limited changes its name to Redbank Copper Limited.

Redbank Copper Limited

http://www.redbankcopper.com.au/projects-and-resources/redbank-copper-project.html

accessed 17 December 2011